Wordless Wednesdays

Field Notes: Adventures in the Temple of the Moon

In the middle of a sand-filled plaza surrounded by decaying walls, a coarse jumble of black boulders spills out of the ground like it was just disgorged by the volcanic peak above. A crowd gathers at the edges, peering at the strangely garbed figures processing with agonizing slowness across the sacrificial platform. An ominous sound fills the air.

Beep.

Beep.

Beep.

Other than sweat and possibly tears or blood, there are no sacrifices today, just scientists in robotic get ups working to figure out what lies beneath the surface at Huaca de la Luna, the Temple of the Moon. You’ll have to forgive the title that sounds like a lost Tintin book; this is where I spent two weeks of my summer this year, listening to the near constant “beep” of ground penetrating radar pulses, hauling equipment, and in between, exploring one of the most impressive archaeological sites in the Americas.

Haiti 5 Years Later

This week was the five year anniversary of the earthquake which left Port au Prince and much of Haiti devastated. It was a magnitude 7 event, caused by a strike-slip fault rupturing 8 miles beneath the surface and releasing waves of seismic energy – we talk about it now and then in some of my classes. Describing the technical aspects from a seismology viewpoint doesn’t much get at the heart of what happened after that, though. Estimates of the casualties range from 160,000 to 300,000 killed, with one third of Haiti’s population of 9 million directly affected, and $8 billion in damages. Recovery over the last few years has been slow, with one physician working in Haiti diagnosing the problems caused by the earthquake as “acute-on-chronic.” The severity of the damage – physically, socially, and economically – was greatly exacerbated by already existing chronic problems in the country.

“Acute-on-chronic”: one of the acute symptoms would be the number of buildings that collapsed due to the quake – some 250,000 homes. The amount of destruction is an expression of the chronic problems of rapid urbanization, unsafe construction, and lack of building codes meant to resist seismic hazard. The issue can be traced further; high rates of urbanization followed the collapse of the agricultural industry in Haiti after American subsidies of US rice farms flooded the market with cheap rice – something that Bill Clinton apologized publicly for in the months after the quake. Tetanus cases from injuries in the quake were widespread largely because of failure to vaccinate. The health system was overwhelmed by the disaster, then by the cholera epidemic which followed. Haiti hadn’t had a case of cholera in over a hundred years; it was spread from foreign aid workers.

Haiti leads the Western Hemisphere in ratings of poverty, health, and water security, and any attempt to address those problems needs to look at the history that contributed to them, from the coups and turmoil of the 1980s and 1990s to the exorbitant reparations required by France after Haiti’s revolution cost the French much of their slave trade. In the aftermath of the earthquake, donations and aid poured in, but this week op-eds have abounded on where that money has gone and why more progress hasn’t been made. Of $1.5 billion from USAID, only 1 cent out of every dollar went directly to Haitian organizations; money instead went to international contractors who cost 5 times more than local workers. Providing funds directly to Haitian organizations or government agencies is apparently a sticking point for foreign donors, who have resisted contributing to a UN proposed trust fund that would be controlled by the Ministries of Health and Environment. Complicated problems can require clever ways to address them – I remember reading about aid workers in the immediate aftermath using Google Earth to track what areas needed help because the blue UN tents were visible in satellite imagery. But it seems that having people on the ground who know what they need and what will work, instead of foreign contractors, is a key point. The Health Ministry is one of the few that does receive direct funding, and has apparently made large amounts of progress in HIV treatments and child vaccinations.

If you have a moment or the means to donate, some of the groups doing the best work in Haiti are Partners in Health and Zanmi Lasante, the local Haitian extension of PIH; they run 12 hospitals and clinics in Haiti, and were some of the first medical professionals on the scene after the earthquake. ZL is the largest nongovernment health care provider in Haiti, with a staff of 5,400 Haitians serving 1.3 million. Currently, there is a quiz on the PIH site about maternal health; for everyone who takes the quiz, 50 cents will be donated: http://act.pih.org/page/s/quiz?source=tout&subsource=tout_country

I also recommend water.org; they help provide clean water and sanitation proposals, working with local organizations from proposals put forth by the communities themselves: http://water.org/country/haiti/

Some sources:

To Repair the World, Paul Farmer

WHO: http://www.who.int/features/2013/haiti_pentavalent_vaccine/en/

http://www.theguardian.com/world/2010/mar/04/haiti-aid-workers-google-earth

AGU2014: Frack Quakes, Black Riders and Failing with Grace

Like wildebeest through the Serengeti, the common Homo geologicus make their way through San Francisco International Airport in droves, identifiable by ever-present poster tubes, hiking boots, and a tendency to flannel. It is once again that time of year, for the long migration known as the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union.

Or rather, it was that time of year, since the conference was before Christmas. About 25,000 geoscientists come to this every year, including myself this year; I was presenting a poster on my undergrad research in Tanzania. The posters and talks available are innumerable, so the first challenge is figuring out what to go to first, but the main themes I followed this year were energy, climate, and induced earthquakes related to energy projects.

Fracking Frenzy Threatens Developing Nations

Excellent post on the risks fracking poses to developing nations; in NY we’re used to thinking of this as a local issue because of its prominence here, but it is a much wider problem.

The Weather Outside is Frightful

~ And Denial is So Delightful ~

I’d like to give a warm shout out to all my friends soldiering through in Buffalo with your literally above my head levels of snow – at this point you should probably consider giving in and hibernating through the rest of the year. No one will judge. Even for upstate and our beloved lake effect, this week’s storm was intense for this time of year, though sadly Ithaca remains almost entirely snow free. The weather was quite apropos considering the activities this week at Cornell, which was a busy one so far as climate change and its effects were concerned. The president of Iceland was visiting, and hopefully felt right at home. The weekly department seminar was as relevant a topic as you could hope to have for a presentation: “Has a warming Arctic contributed to colder winter weather in the Northern Hemisphere mid-latitudes?”

Rules for Fieldwork, Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Embrace the Benefits of Mud Baths.

Everybody’s got to have to have rules to live by, right? Here are a few things that seem to have recurring usefulness for this sort of thing.

1. Never pass up the opportunity to eat, sleep, or use a toilet.

2. Batteries: fear them, and their potential ability to blow you and/or your car up should you forget to tape the terminals.

3. Just because it’s not your mess doesn’t mean you don’t have to clean it up.

4. Never take anti-malaria meds on an empty stomach, particularly before 6 hour car rides. And if you do, hope there are barf bags available.

5. Why pack multiple pairs of pants that will just get dirty when you can wear the same pair for 2 weeks straight?

6. If you don’t wear a wide brimmed hat and sunscreen of the appropriate SPF, Indiana Jones appears and beats you with his whip.

7. Field notebooks – it’s only science if you write it down! No joke here, the slow march of dirt and destruction across formerly pristine notebooks is one of my favorite things.

8. No matter what you read in outdated textbooks, don’t actually lick or eat your field samples.

9. Never go anywhere without your knife.

9a. Or duct tape.

9b. Or your own personal roll of toilet paper.

10. In case of dinosaur attack, remember to remain motionless at all costs.

11. And in case the Ark of the Covenant actually does turn out to be in Ethiopia, unleash on the nearest neoNazis or bigots of your choice!

Field Notes: Ethiopia

Before I fall too far down the rabbit hole that will be my attempts to make up for missing two weeks of the semester for field work, here are some thoughts on my trip to Ethiopia. Yes, it was awesome; no, I do not have ebola; yes, the food was great.

After an unexpected 16 hour layover in Washington DC, my labmate and I arrived in Addis Ababa on the evening of the 16th, ready for the nearest bed. The first morning I was in Addis, we overslept and had to roll out the door to make our meeting with our colleagues from the University of Addis Ababa, and were then thrown into a busy day of packing and shopping. The second day, though, I had the chance to take in a foggy morning panorama of the city from the hotel balcony; joggers passed below to the sound of the morning call to prayer from a nearby mosque. We left that second day for the countryside, skipping breakfast so that we could avoid the morning rush hour – a debatably successful tactic, seeing how the highway at that hour wasn’t full of cars but of boys playing soccer in the lanes. We stopped outside the city for breakfast and coffee at a restaurant with a decommissioned EthiopianAir plane parked next to it; the seating inside consisted of the airplane seats. A cute idea, but less welcome after two days of flying.

Procrasti-writing at its finest

This started out as a short-lived study-abroad blog when I was in Edinburgh, and then was briefly updated last year during my Take 5, mostly because my adviser asked me to write something she could show the NSF to demonstrate the benefits of taking undergrads into the field. I had the idea at the time that I would keep up writing posts to document my T5, but that fizzled right off the bat, because there’s nothing I like more than not doing things I don’t need to do. I thought about starting it up again this past summer, what with graduation, some fun field work trips, and starting at a new school, but see the aforementioned statement about doing things. Doing things is the worst.

However, it’s just over a month into the semester now, and I’m once again rethinking this blog thing. For one, it’s fellowship application season, and I’ve realized just how rusty my writing skills are right now. More importantly though this month has made me realize just how much grad school is going to shift the balance in my life. I double majored in English because I really enjoy both writing and studying literature, and between that and Take 5 I’ve never had to buckle down and just study one thing exclusively as I am now. It’s geology all day everyday, except when there’s math. Not complaining about too much science (just the math, definitely the math), but I do miss the ability to explore a range of interests within my studies and I’m realizing it’s going to take a lot more work now to maintain that. So I’m thinking that I can use this blog as a way to keep writing and include some wider topics rather than just working in the lab all day and turning into a sloth the rest of the time. In keeping with a long tradition of shame-induced productivity, I’m hoping that having declared my intentions I’ll be honor-bound to follow through. There will probably be some stuff on environmental topics, maybe some geology or archaeology related news, or just whatever is going on here.

A bit of an update: I’ve been at Cornell since the end of August, and other than busy-ness it’s been great so far. I’ve got an idea where my research is going – I’ll be studying how earthquakes can be caused by human activity like fracking or the creation of reservoirs. I love UR and everyone there, but when I’d say I was a geology major the most common response was “Oh, I didn’t know we did that here.” Whereas Cornell often seems like one massive, life-scale laboratory for every aspect of earth sciences. I hiked along one of the gorges last weekend and could have been in complete wilderness, except that every mile or so would be a sign for things like the “Cornell Wetlands Management Project” or the “Forest Farming Research and Education Center,” also known as the MacDaniels Nut Grove. The benefits of being a land-grant institution…You want rock cut gorges? We got twenty. We’ve got soils and crop science galore. Solar panels and lake source cooling for AC? Plenty.

But who cares about that – I also have some tragic news; I will not be able to make it to Meliora Weekend this year, alas. From Oct. 14 to 29 I will be doing fieldwork in Ethiopia; this will be similar to the work I did in Tanzania, but a whole new environment and group of researchers. So most likely the next post I make will be a recap of that trip! Which I have not properly packed, prepared, or received a visa for yet, so back to work!

Half a World Away from the Olduvai Gorge

These days, you can judge how well my day has gone by the number of times I’ve listened to “This Year” by the Mountain Goats – I’m going to make it through this year if it kills me. I haven’t even started applying to schools yet; it’s all been fellowships so far. As my next round of deadlines approaches, for the NSF Graduate Fellowship application, I’ve also been thinking near constantly about my trip this summer to Tanzania and Olduvai Gorge, with the “Soudoire Valley Song” as an appropriate soundtrack (see title). For the research proposal section of my application, I am designing a seismic survey of Olduvai Gorge and the surrounding basin. The proposal is mostly theoretical, a way for reviewers to see that you know how to properly approach and address a research problem, but the more work I do on this, the more I really want to make it a reality.

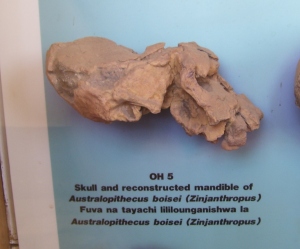

For a little background, Olduvai Gorge is a World Heritage Site in northern Tanzania that has yielded some of the most important paleoanthropological finds related to human origins in the 20th and 21st centuries. Some of the first researchers to take a close look at the gorge were Mary and Louis Leakey, who made such discoveries as a 2.6-1.7 million year old stone axe culture and the 1959 find of the Zinjanthropus boisei hominid skull. During his work at Olduvai, Louis Leakey started the career of the incomparable Jane Goodall, wanting someone to study chimpanzee behavior so that it could be used as a basis for conjecture about early hominid behavior. There was little time for sightseeing this summer, but if I’d had the time for a flight followed by a 3 hour water taxi ride, I’d have visited the Gombe Stream National Park, site of Dr. Goodall’s chimp observations and research center. Leakey also started Dian Fossey and Birute Galdikas on on their work with gorillas and orangutans for the same reason. Geologically, the Gorge is also a very important locale; located on the flank of the East African Rift where the continent is pulling apart, it contains layers of volcanic lavas and ash flows from the Ngorongoro Volcanic Highlands, which includes the world’s largest intact volcanic caldera, Ngorongoro Crater, and the active Oldoinyo Lengai volcano. Nearby at the site of Laetoli, there are actually fossil footprints of bipedal hominids preserved in the ash. Faulting and tectonic activity in the basin relates to the formation and expansion of the East African Rift.

You can see why I’d be excited about being there, and about the possibility of going back. Talking with a researcher who works on excavations in the gorge, it seems like there could be a lot of use for the type of project I want to do; a seismic survey would create a profile of rock layers up to 1 km deep in the subsurface, and it would provide a lot of information about the structure of the gorge and possibly determine new directions for excavation to take. As I’ve been doing the background research for my proposal, I keep realizing how little is actually known about the area, despite the better part of a century’s worth of field work. There has been little to no geophysical work in the area, except for the CRAFTI seismic array from this year, and none concentrating on the archaeology sites. Outlining this proposal has also made me do a lot of thinking about what I want out of graduate school and a research career; while I’m interested in the use of geophysics in archaeology, there is not a lot of work done by researchers in the US in that specific field. In the case of Olduvai, however, the intersection of geology and archaeology that the gorge provides, with its implications for continental rifting processes, rift related volcanics, and human origins, is a fascinating problem to delve into (and, hopefully, get funded by the NSF which technically doesn’t fund straight archaeology projects), and whether I get this fellowship or not I hope I can be back in the field there before too long. That’s the one good thing about having to write strict-3-page-limit-tell-us-everything-about-your-life-and-hopes-and-dreams-and-also-career-plans essays; I’m getting a much better grip on what’s important enough to go in them, and I think Olduvai Gorge is one of those things.