[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”11″ display=”basic_imagebrowser”]Viewable as a pdf here: bit.ly/Fodienda

Bad Neighbors

A Little Girl Tugs on a Tablecloth

[ngg src=”galleries” ids=”9″ display=”basic_imagebrowser”]Illustrations for a poem by the wonderful Polish poet Wisława Szymborska, dedicated to my baby niece.

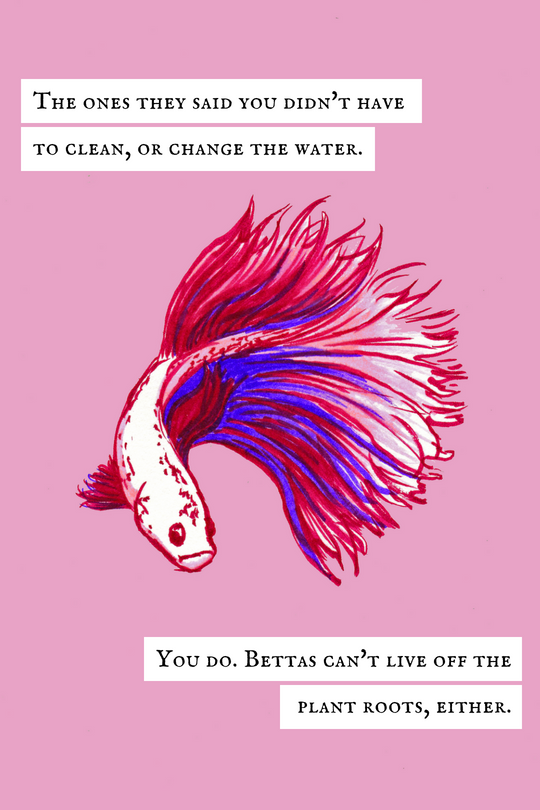

Fishes Wobble So They Don’t Sink Down

Do Betta

Bettas deserve better.

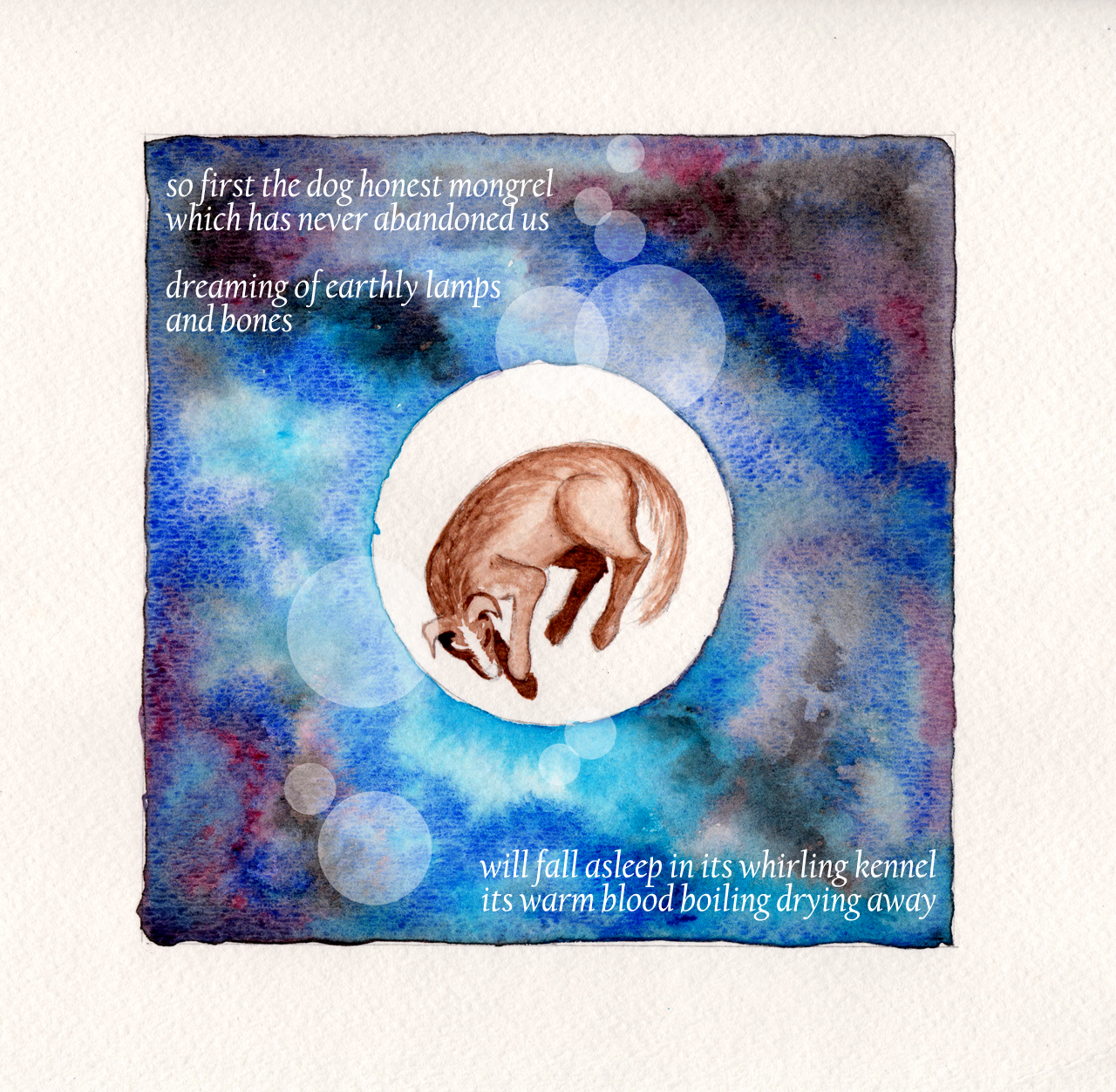

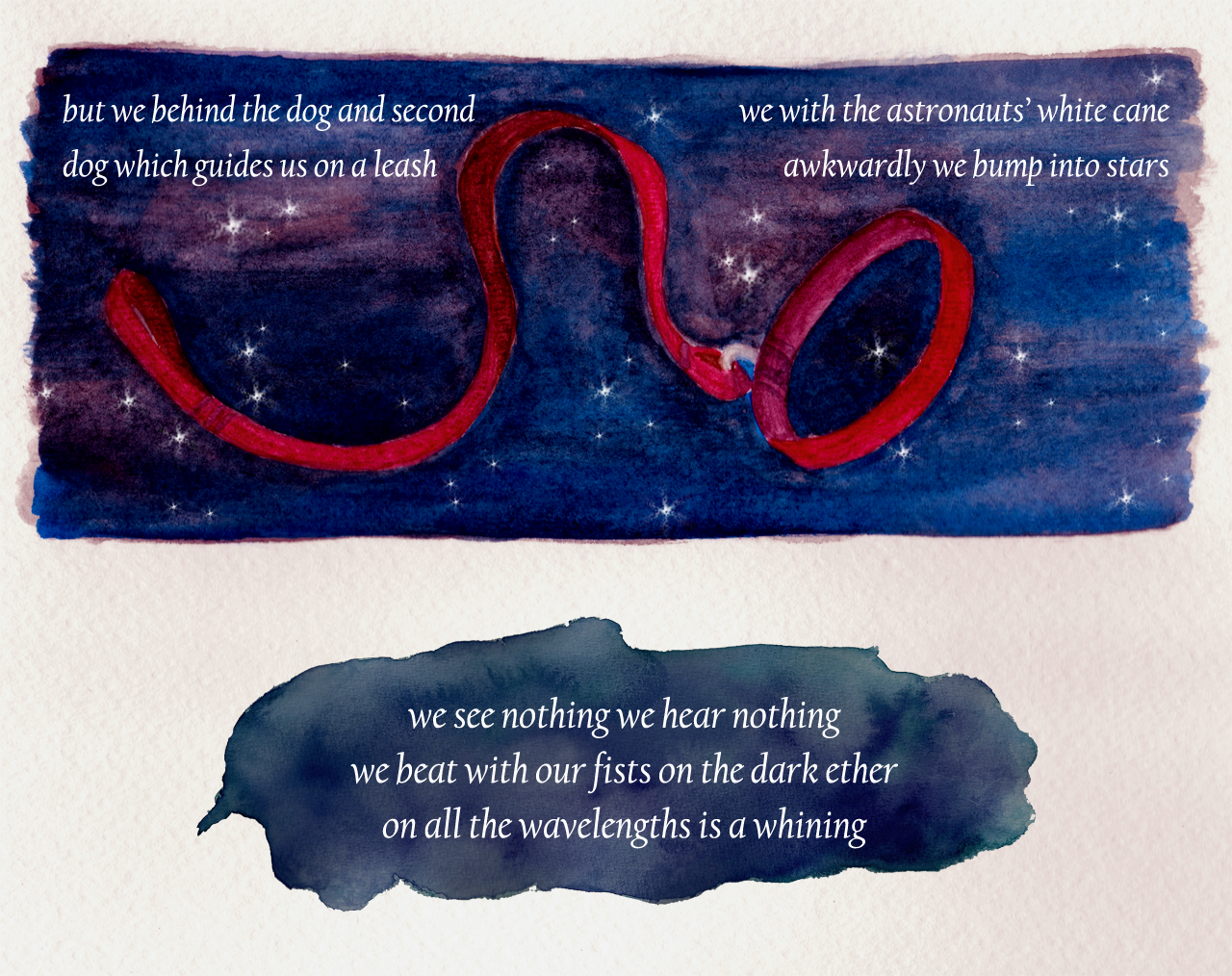

First the Dog

Speaking of the Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert, Robert Hass said that Herbert wrote “as if it were the task of the poet, in a world full of loud lies, to say what is irreducibly true in a level voice.”

Zbigniew Herbert (yes, that’s how it’s spelled, yes the names go in that order) came of age during the Nazi occupation of Poland, writing his first poems while a member of the Polish resistance. The introduction in my volume of his poems describes his work as “quarrying for himself a little area of light and sense in the engulfing darkness of total war and repression.” Even while ruminating on the fate of Laika, the Moscow stray sent to space in Sputnik 2, Herbert’s meticulous lines cast out a light into the unknown, into the blind darkness of space, tracing a path forward towards the future of space exploration.

From “Selected Poems,” translated by Czeslaw Milosz and Peter Dale Scott, 1968.

Noli Me Tangere

Sagittarius serpentarius – it’s got style, glamour, and a kick with a strike force 5 times its own body weight. The etymology of its common name, the secretary bird, is fuzzy; some sources say it refers to the long, quill-like plumes on the bird’s head, others that it stems from the Arabic saqr-et-tair, for hunter. With the longest legs of any bird of prey, these birds hunt terrestrially and are known for stomping their prey to death before eating it whole. It’s an admirably efficient process. They are particularly famed for killing snakes this way, referenced in the scientific name Sagittarius serpentarius, which means “archer of snakes.” I saw secretary birds throughout my trips to Tanzania, their stork-like height coupled with the heavy body of a raptor making them stand out on the savanna. Any large bird carries a gleam in their eye that says “We haven’t forgotten being dinosaurs,” but I think that, next to ostriches and emus, secretary birds may remember it the best.

The phrase “noli me tangere” is Latin, loosely translated as “don’t touch me” or “stop touching me/cease clinging to me.” It was a popular trope in medieval Christian art, depicting a scene in the Bible after the resurrection when Jesus said the phrase to Mary Magdalene. Derivations through the years include the Gadsden flag’s “Don’t tread on me,” with its aggrieved Revolutionary rattlesnake that has been appropriated in the modern era by the Tea Party and others who think that lifting a boot from someone else’s neck is the equivalent of having their own toes stepped on. While I do think that snakes – rattlesnakes in particular in the U.S. – get a bad rap, I wanted to flip the script from the static “don’t tread on me” – a fear of uncertain future attacks – to the older translation: stop touching me. The snake in the grass is doing me harm, here and now, and it’s going to stop. Time’s up.

Some sources:

http://animals.sandiegozoo.org/animals/secretary-bird

http://library.sandiegozoo.org/factsheets/secretary_bird/secretarybird.htm

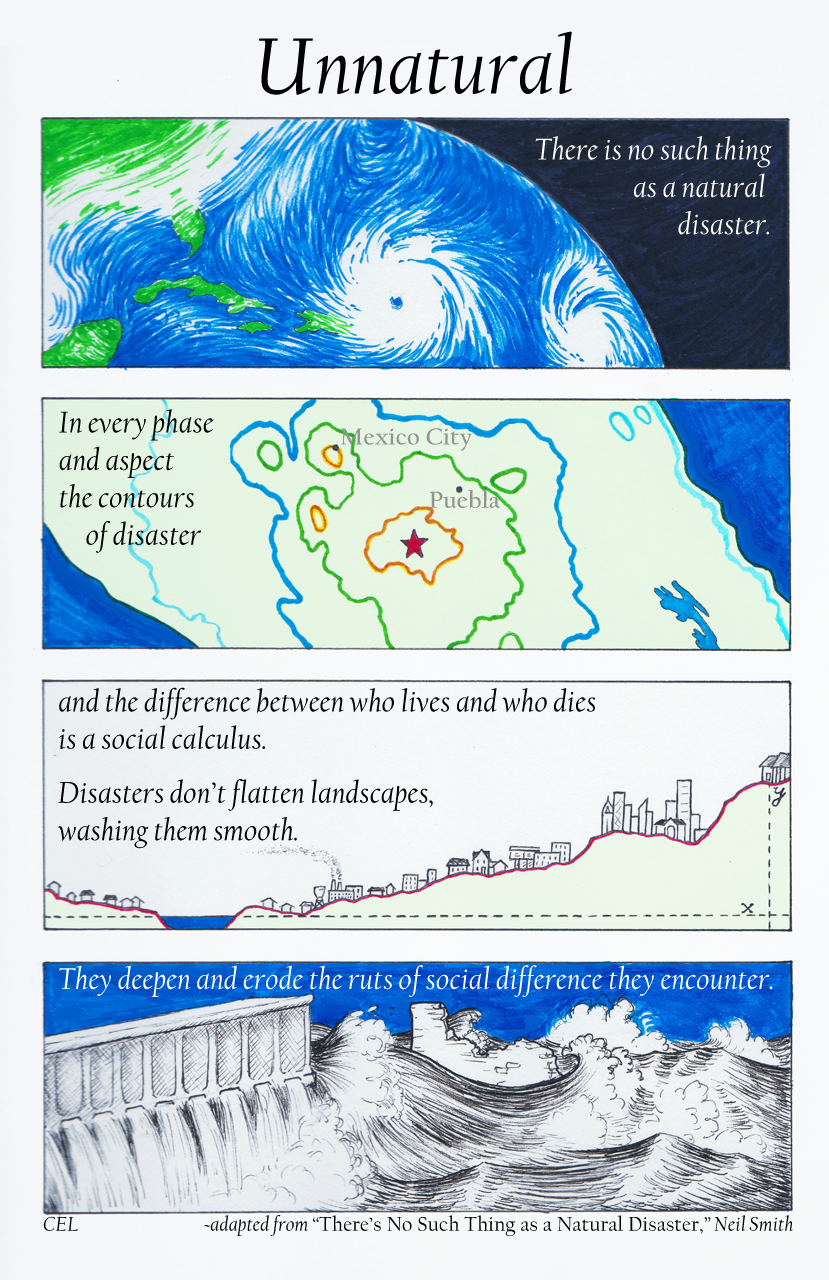

Unnatural

“It is generally accepted among environmental geographers that there is no such thing as a natural disaster. In every phase and aspect of a disaster – causes, vulnerability, preparedness, results and response, and reconstruction – the contours of disaster and the difference between who lives and who dies is to a greater or lesser extent a social calculus.”

This essay and others at Understanding Katrina were written in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, addressing the political and social issues laid bare by the devastation. They call the supposed “naturalness” of disasters a form of ideological camouflage for the fact that many dimensions of a disaster are preventable.

Even when the hazard itself is natural, like the earthquakes devastating Mexico, the effects are socially determined. Meanwhile, the battering ram of hurricanes in the last month was doubly so, exacerbated by the unnatural role of climate change that the government and special interests continue to let go unchecked. It’s easier – and more convenient – to dismiss disasters as an Act of God than to address them as failures of government, infrastructure, and preparedness.

Nettled

In Book I, Part V of Les Miserables, we are reintroduced to Valjean as Mssr. Madeleine, who, in between committing a series of agricultural good deeds, pauses to spend a near full page amiably lecturing the local farmers about the beneficial uses of nettles, with a less amiable aside on the failings of society. As a character moment, I’ve always been fond of this quote in its gentle ridiculousness, but it also quietly captures not only Valjean’s worldview but also the broad theme of the book, the vast potential that is snuffed out by the failures of an oppressive society that doesn’t just neglect the powerless and unfortunate, but actively rips them out by the roots.

What has the EPA done for NY23?

Last week, as Scott Pruitt tried to defend the proposed decapitation of the EPA in front of the House Appropriations Committee, both Democrats and Republicans made it clear that the elimination of 50% of the EPA’s programs and 31% of its budget wasn’t going to fly. Lawmakers on both sides cited the damage to their home districts that would be done by removing federal support for environmental protections and programs. Projects countering chemical contamination, water pollution, and ecological degradation are popular, like the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, a multi-state program which was slated for elimination earlier this spring. A bipartisan group of representatives from districts around the Great Lakes signed a letter calling for the GLRI’s continued funding, but missing from the list of signatures was Tom Reed of my district, NY 23rd. Reed, a well-entrenched and vocal supporter of 45, has a long history of opposing environmental protections in favor of industry (more at the New NY 23), and of opposing his constituents’ best interests in favor of his own. In light of this, it seems like an appropriate moment to take stock of what the EPA has done in this district.

The map above shows the grants disbursed in the NY 23rd since 2007. In the last ten years, grants from the EPA to cities, towns, school districts, tribal nations, and universities in our district have totaled almost $40 million. Continue reading