Speaking of the Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert, Robert Hass said that Herbert wrote “as if it were the task of the poet, in a world full of loud lies, to say what is irreducibly true in a level voice.”

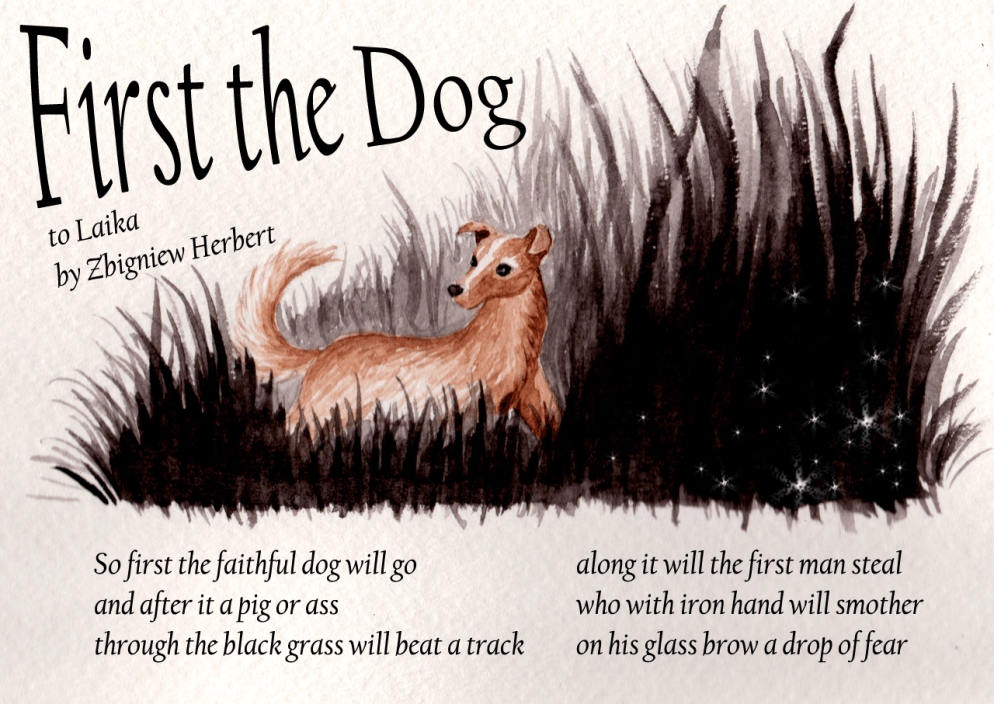

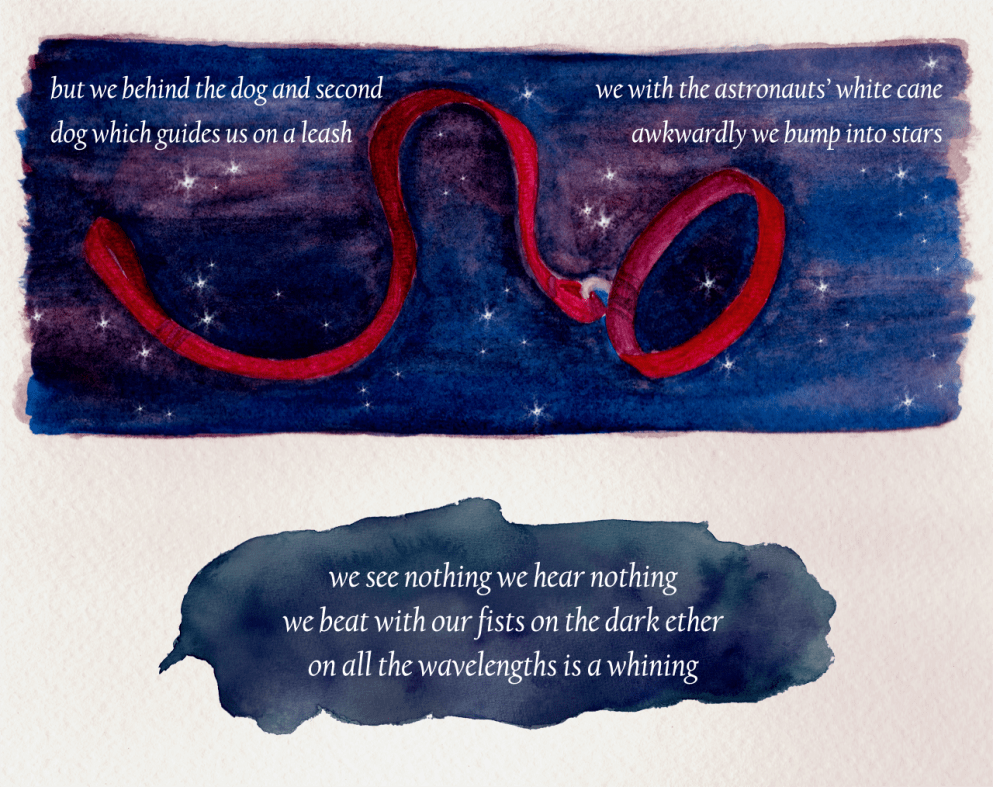

Zbigniew Herbert (yes, that’s how it’s spelled, yes the names go in that order) came of age during the Nazi occupation of Poland, writing his first poems while a member of the Polish resistance. The introduction in my volume of his poems describes his work as “quarrying for himself a little area of light and sense in the engulfing darkness of total war and repression.” Even while ruminating on the fate of Laika, the Moscow stray sent to space in Sputnik 2, Herbert’s meticulous lines cast out a light into the unknown, into the blind darkness of space, tracing a path forward towards the future of space exploration.

From “Selected Poems,” translated by Czeslaw Milosz and Peter Dale Scott, 1968.